The Hermitage

The Hermitage (250+ Years of American History)

THE NATIVE AMERICAN INHABITANTS IN AREA OF FUTURE HERMITAGE PROPERTY

Their Way of Life

The first people on the property that was to become the Hermitage were the Native Americans. When the Europeans arrived in the 17th century it was the Hackensacks, a group within the Lenni Lenapes, who were living in the current central Bergen County area. A considerable number of Native American artifacts have been found along the Ho-Ho-Kus Brook which bordered the Hermitage property. On the property itself a stone axe, a bowl and arrowheads have been found. These indicate that various Native American people hunted and fished and probably at times resided on this land.

Settlement of Area by European Invaders and Settlers

The first Europeans to claim this area were the Dutch as part of New Netherlands. Then, when in 1664, the English conquered New Netherlands, it became the domain of the Duke of York. He granted what became East Jersey to Lord Berkeley. After the Lord’s death, his widow sold East Jersey to a group of 12 Proprietors, some of whom were English, but most of whom were Scots. They established their colonial base of operations in Perth Amboy.

Exclusion of Native Americans from the Area

Despite the claims of the Proprietors, a group of French Huguenot merchants and land speculators in New York City under the leadership of Peter Fauconnier, bought a large section of what is now northern Bergen County, the Ramapo Tract, from the Hackensacks in 1709.

PIONEER SETTLERS ON HERMITAGE PROPERTY

The Traphagen Family – Jersey Dutch Settlers – 1740s

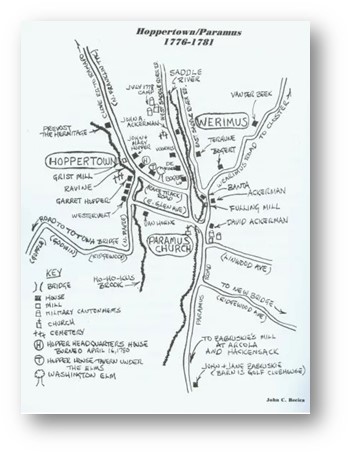

The property that was to belong to The Hermitage was on the southwestern edge of the Ramapo Tract. The first settlers in the general area of The Hermitage were the Hopper, Bogert, Ackerman, Oldes and Terhune families of Dutch ancestry. A small settlement would be called Hoppertown (Ho-Ho-Kus). Just to its south, the Paramus Dutch Reform Church was built in 1735. There was a rudimentary road that had previously been a Native American path that ran from Hackensack through Paramus and Hoppertown north to the Clove above Suffern through which ran the Ramapo River.

The first individual owner of record of The Hermitage property was Johannes Traphagen. There is not concise documentation on when he first settled there. The first mention of his name is found in a 1743 report to the Proprietor’s by its surveyor John Forman when he wrote about land located between Hopper’s and “John Traphangle’s mill.” In 1744 Forman wrote that John Traphangle had 100 acres near Hopper and Oldes. In the following year the Proprietor’s records have Johannes Traphagen and his heirs as owning 102.79 acres.

Traphagen was born in Esopus, New York, one of ten children. His family, in all probability, was descended from settlers in New Amsterdam. He married Marrieti Laroe in Paramus in 1734. She was born in Rempoch (Ramapo) and baptized in 1719 in the Hackensack Dutch Reformed Church. Her father was Henry Laroe (1685-app1766) and her mother was Marrieti Smidt who was from Tappan. The Laroes were French Huguenots. The origins of the Traphagens is unknown. They may have been of French Huguenot or Dutch ancestry.

Johannes and Marrieti, as the first settlers on what would become The Hermitage property, faced the challenges of being pioneers that needed to fashion a home and a supporting farm out of the forest wilderness that they had acquired. They needed to engage in the strenuous work of felling trees in order to have materials to build a shelter and for fuel for cooking and heating. They had to clear land of trees and rocks so they could engage in farming for their food supply. Afterwards, additional crops allowed for some trade so they could acquire nails, tools, and other things that they could not make themselves. Before the land produced, and even afterward, food was also obtained by hunting, fishing, and gathering. There were still a few Native Americans in the area as well as the forces of nature with which they had to contend. In 1757, there was a major flood in the area. But the Traphagens did succeed in building a home, a producing-farm, and a family. They altered the environment and began to establish for the area a new type of social and economic life.

Before 1760 Johannes Traphagen’s eldest son Henry had married Claaritje Hopper at the Paramus Church. She was the daughter of Jan Hopper and Rachel Terhune of Hoppertown. When Johannes died in 1760, Henry petitioned the Proprietors for his half share of his father’s 100 acres with the other half to go to the other children of Johannes.

The Lane Family – English lawyer and Land Speculator – 1760

However, one, Henry Lane, also claimed what would become The Hermitage acres. He was an attorney and an agent for the West Jersey Society. He may have been related to Thomas Lane, one of the members of the Committee of the West Jersey Society. Thomas’s grandfather was Sir Thomas Lane, Knight, and Alderman of London. Henry Lane appears to have been an affluent land developer and had a house in New York City. Around 1760 he acquired the property of Johannes Traphagen. Lane apparently purchased the land from an intermediary who it was claimed had purchased it from Traphagen. In all these dealings, there were disputed title claims.

The Lane’s Build a New House that Would later Be called The Hermitage – 1760

Henry Lane and his wife Elizabeth quickly improved their 105-acre Bergen County property with a new stone dwelling house in addition to a small barn, a gristmill, a sawmill, a young orchard, and cleared arable land. It is not known if the Lane’s built an entirely new house and made the Traphagen residence an outbuilding or if they incorporated that former house into the new home. It is believed that the new Lane house is the one which will become, within the next decade, The Hermitage. The Lanes brought a new ethnic and social dimension to the Hoppertown area. They were a family of English background amongst primarily Jersey Dutch neighbors, and they brought a more well-to-do, professional way of life into a farming community not long removed from frontier conditions.

According to the records of the Paramus Reformed Church, the Lanes had their son William Henry baptized there on August 1, 1762. They also had a daughter Greesle Lena. The records also show that Henry Lane made out his will on December 27, 1762, apparently a deathbed will. It was proved on January 29, 1763. By February, his wife had decided to put up for sale both the Bergen County and the New York City properties. Elizabeth Lane, Executrix, placed a for sale advertisement in the February 28, 1763 issue of The New York Gazette:

A choice Plantation at Ancocus Brook, (or a Place called Peramos) in the county of Bergen, and Eastern Division of the Province of New Jersey; containing about 105 acres of good arable land, part of which is cleared, the remainder well wooded; there is on the same a good new Stone Dwelling House 40 foot front, and 23 foot back, the front is all of hewn stone, a Cellar under the Whole, and a Well of good Water before the Door; the Walls are near two Foot thick, and good Sash Windows to the House; there is also a good Kitchen 23 Foot one Way, and 20 Foot the other Way, and a good Fire-place therein; The House contains four Fire-places and is two Story high, is pleasantly situated between two Main Roads, and has an entry through the House into the Kitchen, all very beautifully contrived: There is also on the said Tract a small Barn, a good Gristmill, and a good Sawmill, all in good Order, and has not wanted for Water in the driest times; there is likewise a thriving young Orchard on the same, >tis as publick and pleasant a Place as is in the Country fit for Merchant’s business, a Tavern, or any other business. Also a Dwelling House and Lot of Ground in the City of New York…Any Person inclined to Purchase the Whole or either of the said Premises or to hire the same, may apply to Elizabeth Lane, at the House of Mr. William Rousby, near the Oswego Market, and agree upon reasonable Terms. An indisputable title will be given.

The Proprietors warned people not to buy the land so advertised, because they still held title to it. Nevertheless, Elizabeth Lane again advertised the property in 1766.

THE PREVOSTS: LATE COLONIAL AND REVOLUTIONARY WAR ERA

Property and House Purchased by Captain James Marcus Prevost in 1767

James Marcus Prevost in 1767 bought 155 acres of apparently unoccupied land, part of which fronted on the Ho-Ho-Kus Brook and part of which adjoined the Lane property. Later that year Prevost also bought 98 acres (5 went to Benjamin Oldes) from Elizabeth Lane, but only after there was agreement on title and payments due among the Traphagen heirs, Lane, Prevost and the Proprietors. The ownership of The Hermitage by Prevost also is verified in the Bergen County Road Returns which state in 1767 that Clove Road runs along Col. Prevost’s property.

The Military Prevost Family – from Switzerland by Way of England to America

James Marcus Prevost (anglicized from Jacques Marc Prevost) was a British officer stationed in North America since early in the French and Indian War. He was born in 1736 in Geneva, Switzerland into a family that had earlier roots in Savoy, now part of France. His parents had nine children, including three sons who would follow military careers that would bring them to North America. The two older of the three, Augustine (born 1723) and Jacques (born 1725), would first enter the service of the King of Sardinia and then Sardinia’s ally the Netherlands. It would appear that Jacques Marc joined his brothers in Holland.

Then in 1755, after the defeat of the British forces under General Braddock by the French and their Indian allies in western Pennsylvania and with an approaching war with France, the English Parliament approved the formation of the Royal American Regiment. There were hopes of enlisting Germans and Swiss settlers in America. The officers (up to 50) were to be Protestants from the continent with military experience and who could speak the necessary languages. In1756 the British commissioned Augustine Prevost, a major, Jacques Prevost, a colonel and James Marcus Prevost, a captain. They all were sent to North America with the outbreak of war against France. Jacques seems to have avoided major battles, but James Marcus was wounded in the battle at Ticonderoga in New York and Augustine suffered serious wounds with General Wolfe’s army near Quebec, both in 1758. Both recovered in New York City. Augustine remained active in the Royal American Regiment, particularly in the Caribbean, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

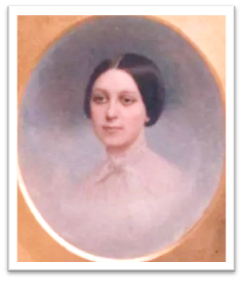

James Marcus Prevost Met and Married Theodosia Bartow in New York City in 1763

James Marcus, after he recovered from wounds, accompanied Colonel Henry Bouguet, another Swiss in the Royal American Regiment, to establish in 1761 a British post at Presque Isle (present Erie, Pennsylvania). They also spent some time at Fort Niagra. Prevost then was assigned to New York City in charge of some of the British troops in that area. However, with the decrease in military activity after the defeat of the French, James Marcus and other British officers in America were put on inactive duty with half pay. While in New York, James Marcus courted and, in 1763, married Theodosia Stillwell Bartow in Trinity Church in Manhattan.

The Family Background of Theodosia Stillwell Bartow – A Five Generation Spectrum of American Colonial Life

When she married, Theodosia Bartow was a young woman of 17 from a well-established extended New York/New Jersey family. She brought to the marriage, and soon afterwards to The Hermitage, a rich, varied colonial North American heritage stretching back more than 100 years. Through her mother she was a fifth-generation member of the Stillwell family from Virginia, New York and New Jersey, as well as a fifth generation Sands from New England and Long Island, and a fifth generation Ray from New England. On her father’s side she was a third generation Bartow from Westchester and New Jersey with some relation to Pells of Westchester and a third generation Reid from New Jersey and Westchester. The Stillwells, Sands and Rays had generally experienced upward mobility from farming into the mercantile and professional class, the Reids and the Pells were land rich and well-connected families, and the Bartows were a well-educated professional family.

The first Stillwell to come to America was Nicholas from Surrey, England who sailed to Virginia in 1638, just 21 years after the first permanent English settlement in North America at Jamestown. He became al tobacco farmer and an Indian fighter. When a trading venture brought Nicholas into conflict with the Virginia authorities, he moved to New Netherlands where he obtained land for farming. His children were also farmers in New York and New Jersey. By the third generation, Richard Stillwell, born in 1762, established himself as a successful New York merchant with a large estate on the Shrewsbury River in New Jersey. He was Theodosia’s grandfather.

Her mother, Ann was the third child, born to Richard Stillwell and his wife Mercy Sands, around 1714. Ann’s brothers and sisters, Theodosia’s aunts and uncles would do well. One uncle became a doctor, and one became a merchant, two of the aunts married British officers, one of whom became a general and both of whom had wealth and standing, two other aunts wed well-to-do merchants, and one aunt married a noted Harvard-educated Presbyterian minister.

Ann Stillwell was brought up on the family’s Shrewsbury estate amid a large, affluent family with extensive family and social connections in New York City. She attained well developed literacy and seemed to have had the advantage of a rather extensive, mostly private education. Shortly after 1742, when she was about 30 years of age, Ann married Theodosius Bartow, about 32, an attorney in Shrewsbury. He owned a 500 acres estate there and additional lands. Bartow was a leader in the Episcopal Church and a man with important New Jersey connections. His father was Cambridge educated, became a minister, and was sent to America to put the Church of England on sound footing in Westchester County in New York. He married Helena Reid, the well-educated daughter of John Reid, the Surveryor General of New Jersey and member of that Province’s Assembly. The Bartows would also marry into the affluent large land holding Pell family in Westchester.

The marriage of Ann Stillwell and Theodosious Bartow was short for he died from a carriage accident in Shrewsbury in 1746 at age 34, while Ann was pregnant with their only child, Theodosia. For five years Ann raised Theodosia as a single parent, apparently partially in Shrewsbury and partially in New York City where several of her sisters and brothers were living. Since two of Ann’s sisters had recently married men with military backgrounds, it appears that she was introduced into that segment of society. Thus, she met and married Capt. Philip De Visme who had served in the British Army, but who had become a merchant in New York City. The wedding took place in 1751 in Trinity Church in Manhattan. Philip was of French Huguenot ancestry and was born in London in 1719. He attended St. Martin’s French Church in that city. His brother, Count de Visme had a daughter Emily who married General Sir Hugh Murray, son of the Earl of Mansfield.

Ann had five children with Philip between 1752 and 1768, half brothers and sisters to Theodosia. In their home French was frequently spoken. When the oldest of the De Visme children, Elizabeth, was only 10 years of age, the father, Philip died in 1762. Ann, at 49, was again a widow, now with six children. Theodosia was then 16 and probably was expected to help her mother with the many young children, although Ann’s financial situation probably enabled her to obtain a considerable amount of service.

Theodosia was brought up both on a country estate in Shrewsbury and in New York City. Her mother gave her the example of a woman who, while not extensively schooled, was certainly well-educated, if not by tutors, then through her family. Ann also transmitted to Theodosia the traditions of several generations of an upwardly mobile colonial family; life supported by urban mercantile and professional affluence and standing; a practiced female strength amidst losses and hardship; and a readiness to seize opportunities wherever they may appear. Theodosia’s stepfather, Philip De Visme, brought a transatlantic cosmopolitanism into the home with his London and French background and connections, a military heritage, a merchant’s acquisitiveness, a frequent use in the home of the French language, and an interest in books and ideas. There is no record that Theodosia, like her mother, had any extensive schooling, but her knowledge of languages, her analytic abilities and her habits of reading indicate an education at home that was far above that received by most privileged women in the colonial New York/New Jersey area. From her stepfather and from a few of her uncles she was imbued with the traditions of the military, and through their connections introduced to young officers who brought to her the excitement, savoir-faire, and different experiences from England and in the case of Jacques Marc Prevost, also experiences and a heritage of the European continent. Prevost, in his mid-twenties, matured through battle and multicultural travels and associations and having already shown leadership talents, entered Theodosia’s youthful social world.

The First Years of Married Military Life of James Marcus and Theodosia Prevost – 1763-1767

At age 17 in 1763 Theodosia Bartow agreed to a marriage with James Marcus with a wedding in the most fashionable church in the New York area, Trinity in lower Manhattan. New excitement and challenge came to Theodosia very soon after the wedding. Within months her husband was ordered to leave New York with his regiment for Charleston. Theodosia accompanied him there. However, by the end of the year she was pregnant. Captain Prevost then arranged for a change in assignment that enabled him to take Theodosia back to New York where she stayed with her mother. It would seem that despite the move north, the pregnancy did not come to term, or a child was lost in childbirth or soon thereafter, because there is no record of a child born in 1764. Meanwhile James Marcus was assigned to a detachment of troops at Fort Loudoun on the Pennsylvania frontier. This unit, led by a fellow British officer of Swiss birth, Colonel Henry Bouquet, campaigned against Ohio Native American towns in the Muskingum Valley. On this expedition James Marcus was accompanied by his nephew, Lt. Augustine Prevost, an illegitimate son of his brother, Lt. Col. Augustine Prevost. The young Augustine soon married into the land rich Croghan family in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and would be related through his wife’s half-sister to the Indian warrior Joseph Brandt.

The Prevost’s Establish a Gentleman’s Farm and Family Life on The Hermitage Property in Hopperstown in Bergen County in 1767

James Marcus returned to Theodosia in New York in 1765. Given the relatively peaceful situation following the French and Indian War many of the officers, like James Marcus, were furloughed on half pay. He then decided in 1767 to purchase 150 unoccupied acres near Hopperstown in Bergen County adjacent to the Lane property and then the Lane property itself of 102 more acres and the house which they would name The Hermitage. There James Marcus took up the life of a gentleman farmer with his wife Theodosia and a growing family. In order to assist the family with farming, milling and care of the house, the Prevost’s, like many of Theodosia’s affluent relatives and a considerable number of their Bergen County neighboring farmers, obtained at least two African American slaves. There was a newspaper advertisement for a Negro man and his wife who had run away from the house of Mark Prevost in Bergen County in 1774.

FIVE POUND REWARD - Run away from the house of Mark Prevost in Bergen County, on the 29of September last, a negro man and his wife: the fellow is serious, civil, slow of speech, rather low in stature, reads well, is a preacher among the negroes, about 40 years of age, and is called Mark. The wench is smart, active and handy, rather lusty, has bad teeth, and a small cast in one eye; she is likely to look upon, reads, and writes and is about 36 years of age. She was brought up in the house of the late Mr. Shackmaple, of New London, and as she had a note to look for a master it is probable she may make a pass of it to travel through New-England. They took with them much baggage. Whoever takes up the said negroes and brings them to the subscribers, or gives such information t that they may be had again, shall be entitled to the above reward, or fifty shillings for either of them, to be paid by Mark Prevost, Archibald Campbell in Hackensack, or Thomas Clarke, near New-York. October 12, 1774.

Not long after James Marcus’ purchase of the Hopperstown properties, he was visited in 1767 by his brothers Jacques, now a Major General, and Augustin Prevost now a Lt. Colonel. The latter was accompanied by his new and now pregnant wife, Anne, and her father Issac. While at The Hermitage, Anne gave birth to her first son, George. He was baptized at Hackensack Church. The godmother was Theodosia, and the godfather was Issac, father of Anne. George, born at The Hermitage, would become the Governor General of Canada in 1811.

Between 1766 and 1771 Theodosia and James Marc had five children, two boys and three girls who spent their childhood at The Hermitage. The boys were Bartow (John Bartow) born in 1766 and Frederick (Augustine James Frederick) born in 1767. They were to have active futures. Little is known of the girls, Anna Louisa born about 1770, Mary Louisa born about 1771 and Sally. All three died young, Anna Louisa in 1786 and Mary Louisa in 1787.

It seems that soon after the Prevost’s moved to their Hoppertown land and while they were living in the house that Lane built, they began to put up another house down by the Ho-Ho-Kus Brook together with a number of mills. When these were completed, around 1770, the Prevost’s moved there and sold the Lane house and 68 surrounding acres to Theodosia’s widowed mother, Ann De Visme. She was still bringing up her five De Visme children. Their home, on the upland, was called The Hermitage. The Prevost home on lower ground by the brook got the name Little Hermitage. The reasons for the choice of this name are not known. In addition, Peter De Visme, a son of Anne and a stepbrother of Theodosia bought 25 acres in this area.

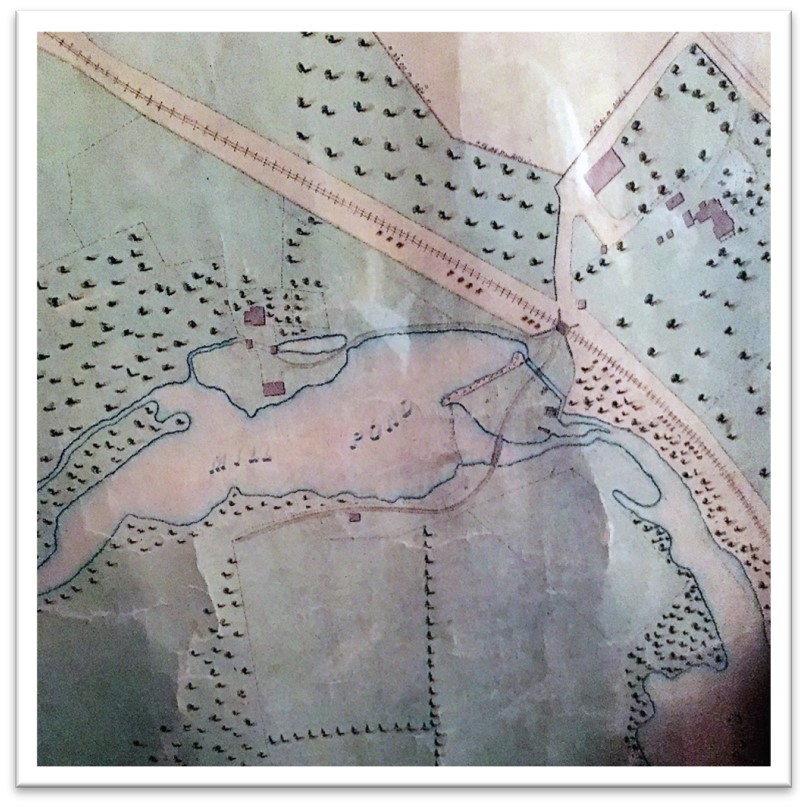

After several years of relative quiet, in 1772 the Royal American Regiment was ordered to the West Indies. In November of that year, James Marcus left from Perth Amboy and sailed to Jamaica to command one of the battalions of this Regiment. He was accompanied by his nephew, Augustine. It seems, though, that James Marc was back in New York in 1773 when he was advertising his Paramus property with a set of new mills and his residence, the Little Hermitage, for sale. Apparently, the advertisement failed, for another one appeared in a New York newspaper in 1774. These advertisements give us some information on the Prevost property just before the Revolutionary War.

A well situated and valuable farm, in the county of Bergen, about twenty-five miles from New-York, on the post road to Albany; there is on said farm a new, well finished house, fit for a gentleman, a large barn, all the outside of which is cedar, and sundry convenient outhouses. Also, a complete set of new mills, on a lively and never-failing stream, with two pair of stones, bolting mills, and conveniences for working them by water; also one or two saw mills, as may best suit the purchaser, who can be accommodated with about ninety acres of land, or more, to the quantity of 240 acres, all round the house. There are several young orchards of grafter fruit, a good garden, and the clear land in excellent new fence, a great deal of it is of stone. An undoubted title will be given for the same, and the terms of payment made easy. For further particulars enquire on the premises, or of Captain PREVOST in New-York.

James Marcus, in January 1775, together with three other British officers, obtained a royal grant of land in New York Province. James’s portion, 5,000 acres, was located just over the Bergen County border and included much of what is today, Suffern. In April he sold his entire patent for 200 pounds to Robert Morris, John De Lancy and John Zabriski. Later, John Suffern was the major purchaser of these landowners. Prevost invested in other properties in New York Province, some in conjunction with Ann De Visme who as a widow could own real estate. These transactions were typical aspects of colonial life in British North America. The acquisition and sale of lands to enhance one’s economic position occupied a considerable portion of the population, and particularly British military officers before the Revolution and more affluent colonials.

The Coming of the American Revolution Divides Theodosia’s Family

At the very time when Prevost, De Visme and the others were engaged in property acquisitions in England’s North American colonies, another very different set of circumstances was unfolding. Questions of taxation, economic opportunities, individual and community rights within the empire, increased local self-rule, control of the western frontier, and quartering of soldiers were issues that since the mid-1760s were increasing friction between the American colonies and England. By the mid-1770s organized local committees of resistance had developed, the Continental Congress was established, an outbreak of hostilities occurred at Lexington and Concord, and a Continental Army was formed.

The impact of events would be dramatic for The Hermitage household. Theodosia, a fifth-generation resident of America had deep roots here, but her husband was an important officer in the British military, as was his nephew and even more his uncle, by then a leading British General. Among the relatives on her side of the family, there were significant splits of loyalty, with most relatives favoring loyalty to the mother country, but some becoming increasingly pro-revolution. Likewise, among the neighbors of The Hermitage, there were mixed loyalties with the Fells and the Hoppers strong Whigs, some of the Zabriskies strong Loyalists and a considerable number trying to remain neutral.

In 1776 James Marcus was called back into active duty with the Royal American Regiment. His brother, General Augustine Prevost had raised a new battalion in Europe for the Regiment, which was first stationed in the West Indies, in Jamaica, then moved to British Florida in 1777 and then into Georgia and the Carolinas in 1778 and 1779. The general’s son, Augustine, was also in this battalion. Additionally, most of Theodosia’s half brothers and sisters were deeply involved with the British. Half-sister Elizabeth was married to an officer who was in the Royal American Regiment with the Prevosts. Half-brother Samuel had risen to the rank of Captain in the British army, and half-brother Peter was a British seaman.

Most of Theodosia’s Stillwell aunts, uncles and cousins were actively or passively pro-British except for Lydia Watkins who left her home in northern Manhattan after its occupation by the British and would move near to The Hermitage for the duration of the war. Her son would be an active rebel officer. In Westchester most of the Pells were Loyalists and most of the Bartows were pro rebel or neutral.

The Revolution and the People at The Hermitage

From the beginning of the Revolution and throughout the war, The Hermitage, being in Bergen County, found itself in one of the most contested areas in America. While Whig militias, and at times the Continental Army, had almost full control of northern Bergen County, and the British, from their major base in New York City and with satellite bases in the southern part of the County, had almost full control of lower Bergen County, the region between was subjected to attacks from both sides. There was much action by local Rebel and Tory militia companies, and there were many incursions and encampments by foraging and attacking Continental army troops and by British and Hessian regulars. Paramus and Hoppertown experienced attacks, skirmishes, foraging, troop movements and encampments throughout the war. In addition, the area suffered from ongoing guerrilla warfare because there were present both active Whig and Tory residents. Neighbors on both sides were killed, wounded, captured, and imprisoned.

Through the war The Hermitage houses and properties were managed by two women and their children: Theodosia Prevost with five children and her mother Ann with her teenage daughter, Theodosia’s half-sister, Caty. There probably also were one or two African American slaves in the household. Theodosia, age 29, took the leadership role. Amid guerilla warfare, the first major challenge for them was survival. The women of The Hermitage were spared attacks from the Rebels because there were no male Loyalists residing there who might fight against the Revolution.

By early November 1776, Washington’s Continental Army had been driven out of New York City. They retreated to White Plains and then decided to cross the Hudson River into Bergen County. After the main British army under General Cornwallis moved into Bergen at Closter, Washington and his troops moved south to Hackensack, to Newark and then across the state and the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. As the British pursued the retreating Continentals through Bergen County they passed within a few miles of The Hermitage.

At Hackensack a contingent of British and Tory troops guarded stored supplies. The American troops left to guard the Hudson Highlands established a base in the Clove just north of Suffern and a supply point in Paramus. Through December 1776 the Rebels attacked Hackensack and the British and Tories attacked Paramus and Hoppertown.

After the British defeats at Trenton and Princeton, they pulled their troops out of most of New Jersey back to New York City. However, in April 1777, the Loyalists attacked Leonia, Paramus and Allendale. General William Alexander with Continental troops camped in Paramus in late July of that year.

The British and Loyalists actions in the vicinity of The Hermitage did not pose a threat to the women there. They could count on immunity from direct attacks by the British, since it was well known that their property was owned by one of their military officers. In fact, the English in 1777 placed a young, captured Rebel medical officer, Samuel Bradhurst, a New York relative of Theodosia by marriage, under house arrest at The Hermitage. He would remain there through the war and would become a good friend of a visitor to the house, Theodosia’s cousin, Mary Smith. Samuel and Mary would marry at The Hermitage in December 1778.

In addition to a concern about security from attack in contested Bergen County, Theodosia and the women of The Hermitage had to face the threat of confiscation of their homes by the Rebels. The property was in the name of British officer Capt. James Marcus Prevost who was actively engaged in fighting against the Revolution. Thus, there were those in New Jersey who wanted to send the women to the British in New York and make The Hermitage a prize to raise money for the revolutionary cause or to reward one of its major officials. Theodosia realized that she had to work actively to counter this threat to her continued hold on her family’s property. She did so with considerable resourcefulness and much courage in her extended battle to maintain control of her family property. She would send petitions to the New Jersey State Whig authorities, she would request leading Whig officials whom she knew or would come to know to advocate on her behalf, and she made The Hermitage a place that welcomed officers of the Continental Army, Rebel militia officers and other Whig persons of rank.

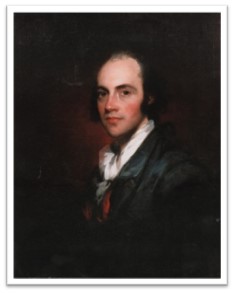

Already in 1777, she was writing for help to people she knew in the influential New Jersey Morris family. Later in that year, in September, when her cousin John Watkins was an officer with the rebel Malcolm’s regiment stationed in the Clove above Suffern, she met its commanding officer, the 20-year-old, Col. Aaron Burr. He stopped at Paramus before and after a daring and successful raid on a British position near Hackensack.

General Washington Is Invited to Make His Headquarters at The Hermitage – July 1778

The next July, the Continental Army, after the important Battle of Monmouth, had marched from New Brunswick and the Great Falls of the Passaic toward the Hudson Highlands with plans to encamp for a rest at Paramus.

As the Continental Army approached Paramus, Washington and his top aides expected to stop and make their headquarters at the home of Lydia Watkins. She was an emigre from New York. With the British occupying her home in Harlem Heights, her husband being abroad, and her son enlisted in the rebel cause in New Jersey, she settled in a house in Paramus with her two daughters and near The Hermitage and her sister Ann De Visme and niece Theodosia Prevost. James McHenry, Washington’s secretary wrote:

After leaving the falls of the Passaic, we passed through fertile country to a place called Paramus. We stopped at a Mrs. Watkins’, whose house was marked for headquarters. But the General, receiving a note of invitation from a Mrs. Provost to make her hermitage, as it was called, the seat of his stay while at Paramus, we only dined with Mrs. Watkins and her two charming daughters, who sang us several pretty songs in a very agreeable manner.

While there, Washington received an invitation from Theodosia Prevost to make The Hermitage his headquarters. The General accepted even though the offer came from the wife of an active British officer.

The invitation read: Mrs. Prevost Presents her best respects to his Excellency Gen’l Washington. Requests the Honour of his Company as she flatters herself the accommodations will more Commodious than those to be procured in the Neighborhood. Mrs. Prevost will be particularly happy to make her House Agreeable to His Excellency , and family C A Hermitage Friday Morning, eleven o’clock.

The army encampment spread throughout the Paramus and Hoppertown area for a four day stay from July 11 to 14, 1778. The Paramus Church served as a resting place for the wounded as well as the site for the ongoing court martial of General Charles Lee. Most of the troops were north of the church with the Commander-in-Chief’s Guard camped near The Hermitage, at “Head Quarters two miles from Primmiss Church.”

Through the four days that Washington was at The Hermitage he had to attend to several issues of crucial significance in the continuing War for Independence. Despite the importance of the recent Battle at Monmouth, he did not have much time to dwell upon it. He was concerned for the proper treatment of the wounded and wanted his troops to have rest after the engagement and the marching in continued oppressive July heat. However, Washington’s mind was primarily focused on the need to decide where to best position his army in terms of potential military moves by the British troops in New York City and in terms of best supplying his men with food and other needs. Very crucially, he had to enter his calculations upon very encouraging news, received in part while at Paramus on July 11th, that a French fleet had arrived off the Maryland coast and was prepared to participate in an action against the British. By the 14th Washington was getting reports that the fleet was off Sandy Hook at the approaches to New York harbor. The fleet was commanded by Vice Admiral Count d’Estaing who was a distant relative of Lafayette. His fleet consisted of 16 ships with from 90 to 36 guns. On the way to New York, they caught a 26-gun British ship and sank it. Washington sent congratulations to the Admiral and two of his aides-de-camps, John Laurens, and Alexander Hamilton, to discuss some possible joint action.

When it was decided that instead the French would attack a smaller British force in Rhode Island, Burr’s spying assignment was terminated and, despite continuing health problems was ordered to rejoin his regiment in the Highlands which marched to West Point in late July. While there, he was selected by Washington to act on instruction from the New York State Legislature and the Commissioners for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies to convey three high placed Tories down the Hudson River under a white flag to the enemy in New York City. They were William Smith, Cadwallader Colden and Roeliff Eltinge, leading members of the former New York Provincial government.

Theodosia learned about this trip. Anxious for an opportunity to visit relatives in New York City, she obtained permission from General Alexander for herself, her half-sister Caty and a man servant for passage on this ship. Burr added their names in his own hand to the Commissioners’ passenger list. With several stops, the trip took from August 5 to 10, providing a considerable amount of time for those on board to become better acquainted, as well as on the return trip.

Burr was kept at the task of escorting Tories and British prisoners to New York on regular trips to New York through September, but he continued to suffer poor health. Thus, he wrote to Washington about resigning from the army. However, Burr decided instead to take a short leave, spending some time with friends in Elizabethtown and some time at The Hermitage. On November 5, Burr wrote a letter to his sister Sally from The Hermitage in which he referred to Theodosia as “our lovely sister.” He continued, “Believe me, Sally, she has an honest and affectionate heart. We talk of you very often, her highest happiness will be to see and love you.”

Meanwhile, Theodosia, after her return to Paramus and together with her mother, continued to keep open the doors of their homes to relatives and friends. One of Theodosia’s cousins who took advantage of this hospitality was Mary Smith, the daughter of Ann’s sister Deborah. Over what was probably a considerable amount of time at The Hermitage, Mary developed a relationship with Samuel Bradhurst, the American officer placed there earlier under house arrest by the British. A courtship ensued and they were married at the end of December 1778 at The Hermitage. They would continue to reside there until near the end of the War. Their first two children, Samuel Hazard Bradhurst, in November 1779, and John Maunsell Bradhurst, in August 1782, were born at The Hermitage.

Despite the joy of the visits and the wedding, Theodosia continued of necessity to be worried about the fate of her mother’s and her property in Hoppertown. Toward the end of 1778 the New Jersey Legislature passed a law calling for the confiscation of land owned by Loyalists and others who were acting against the Whig cause. The Hermitage was a prime target, particularly since Theodosia’s husband and brother-in-law were then leading a British attack on Rebel positions in the southern states.

Theodosia, in the midst of this threatening environment, continued to cultivate people of influence in the state. Through the fall her association with Burr seems to have increased and came to include two of his closest friends, William Paterson, then Attorney General of New Jersey, and Col. Robert Troup. Both men were on friendly terms with Governor Livingston and his family, as well as with State Supreme Court Justice Robert Morris. On January 27, 1779, Paterson wrote from The Hermitage to Burr who earlier that month had returned to military service. General McDougall had pressed Burr to take command of the important but demoralized and poorly disciplined Westchester line. For two months he trained these soldiers, intercepted trade with New York City and engaged successfully with a Tory militia.

Despite this activity and in part caused by it, Burr’s poor health did not improve. Thus, he decided to carry out his deferred decision of the previous fall to resign from the military. On March 10, Burr wrote to Washington that his poor health about which he had informed the Commander the past September, had continued to plague him.

He stated: At the instance of General M’Dougall, I accepted the command of these posts; but I find my health unequal to the undertaking. Thus, I propose to leave this command and the army.

Washington replied on April 3: In giving permission to your retiring from the army, I am not only regretting the loss of a good officer, but the cause which makes his resignation necessary.

After Burr had written Paterson about his resignation, his friend responded from The Ponds (Oakland), some ten miles northwest of Paramus, in which he congratulated him on his return to civil life and suggested that he marry Theodosia. This seems to have been an impulsive estranged letter from a friend to a friend. Paterson is happy with his own relatively new marriage, is happy that his friend has come out of the military still vibrant despite his illnesses and happy that his friend has an affectionate relationship with a woman whom he, Paterson, likes and admires. However, was he really urging his friend into a marriage with a woman who was still married and who Paterson still addressed as Mrs. Prevost?

Paterson, in sending this letter and in proposing a meeting, took it for granted that Burr would be at Theodosia’s home. Following his retirement from the army, Burr attempted to find a way to regain his health and to resume his study of the law. These preoccupations kept Burr from seriously considering at this time Paterson’s suggestion that he marry Theodosia. In addition to her existing marriage, Burr was this time not yet set in an income-producing career. Burr did though help to arrange for Dom Tetard to be a tutor for Theodosia’s three daughters. Somehow, it also was arranged, on the request of James Marcus Prevost, that their two sons, aged 11 and 9, would join him in the south and would become ensigns in his Royal American Regiment. Burr returned to the study of law but continued to visit The Hermitage while Theodosia continued to struggle to protect her home and property

In spring 1779 Theodosia received the unhappy news that her half-brother, Peter de Visme, a British seaman, had been captured and was a prisoner of the American navy. Theodosia, again turning to connections she had made, wrote to Washington to get his release. The Commander in Chief of the American Army replied kindly, but stated that he had no authority relating to the release of maritime prisoners

Another major worry for Theodosia continued to be the preservation of her home and land. Burr wrote to Paterson to ask him to advocate on behalf of her interests. Paterson wrote to Burr on June 1, saying that he had talked with the Commissioners who threatened to confiscate her property.

Meanwhile in early 1779, under the command of Augustine Prevost, now major general, and, second in command, James Marcus Prevost, now lieutenant colonel, some 5,000 British troops attacked rebel positions in Georgia and the Carolinas. James Marcus, who New York Tory Governor William Tyron “spoke of as conceited and vain,” led his troops to important victories in battles at Sunbury and Briar Creek in Georgia. The Prevosts and their troops then took Savannah and Charleston, and in early fall defended the former against a major siege by the French under Admiral Comte d’Estaing and the Rebels under General Lincoln. James Marcus was appointed the Lt. Gov. of the Royal Administration in Georgia and at that time urged Theodosia to come south and join him. Her half-sister Eliza, whose husband was also serving in this campaign and whom she accompanied, also tried to persuade Theodosia to join her and the wives of the other officers. Theodosia, however, decided against leaving The Hermitage on the grounds of her need to protect their property, her poor health, and the best interests of their daughters. She sent James Marcus a ring and a lock of her hair.

The very success of the Prevosts against the Rebels in the south increased the interest of the Bergen County Commissioners for Forfeited Estates to act against The Hermitage holdings. Despite efforts on behalf of Theodosia by William Paterson, the Commissioners served Theodosia with an inquisition, indicating that procedures had begun for the seizure of the holdings that were in her husband’s name. Theodosia, for her part, on December 24, 1779, sent a letter to the New Jersey legislature seeking its support against the Commissioners. They deferred action until their next meeting, when it was read and ordered to be filed, March 9, 1780.

Meanwhile, Burr began his return to law studies in Middletown, Connecticut with Titus Homer, one of Connecticut’s delegates to the Continental Congress. While there, Lt. Col. Robert Troup, urged his friend Aaron to join him in Princeton in a law apprenticeship with Richard Stockton, one of New Jersey’s signers of the Declaration of Independence. However, Troup and Burr came to realize that there would be too many distractions in Princeton from female acquaintances, among whom were the Livingston daughters who showed an interest in Burr. Thus, they decided instead to study with William Paterson. After doing so for a time, they found that Paterson was too busy and traveled too frequently to be able to give the students the attention they desired for rapid progress in their studies. The two aspiring lawyers then decided to study with William Smith in Haverstraw who focused their efforts and under whom they did move forward quickly.

War Activities Continue in the Paramus/Hoppertown/Hermitage Area

Rebel troops were stationed almost continually in the Paramus/Hoppertown area. It was, according to Washington, a post that was part of a network obtaining information on any movement of British troops out of New York, it gave protection to the Continental’s communication route along Valley Road connecting Morristown and the south with New England, it was a base for attacking British positions in the southern portion of Bergen County, it provided some protection for patriots in contested Bergen County, and it was an effort to lessen trade and all types of other dealing with the enemy in New York City. In both March and April 1780 British forces from New York struck into Bergen County and engaged rebel contingents in the Paramus/Hoppertown area causing death and destruction.

The Relationship Between Theodosia and Aaron Grows and Theodosia’s Fight for The Hermitage Is Successful

In June 1780 Theodosia sent a letter to Burr’s sister Sally Reeves in which she called her brother “my inestimable friend.” Letters from Troup and Paterson indicate that Burr was at The Hermitage or at least a frequent visitor there through the summer and into fall 1780. The situation at The Hermitage was such that Aaron’s cousin Thaddeus Burr writing from Connecticut to Paramus stated: “I won’t joke you any more about a certain lady.”

While Burr still needed help in his efforts to recover health, Theodosia continued to need support as she was deeply perturbed when another indictment was issued against the property of James Marcus Prevost, this time by the New Jersey Court of Common Pleas in Bergen County. Paterson, in a letter to Burr on August 31, again pledges his service on Theodosia’s behalf. She had a right to be concerned. Despite the advocacy on her behalf of influential friend’s threats to her property continued. In November 1780 she was informed that “there are Inquisitions found and returned in the Court of Common Pleas, held for (Bergen County) on the fourth Tuesday in October last, against the following persons, to wit, James Marcus Prevost…” Final judgement was to be rendered in January.

However, the issue of confiscation after the fall 1780 inquisition disappears from the extant records and letters of all concerned parties. The indictments against The Hermitage properties were never executed. Apparently, the prolonged advocacy of Burr, Troup, Paterson, and others with Governor Livingston, the Morrises, and additional persons of position seems eventually to have taken effect. The cultivation of influential friends in New Jersey by Theodosia over a considerable period seems to have been crucial in the successful retention of her home and property despite very negative circumstances. It also may have been helpful that Lt. Col. Prevost no longer was in the field against American troops after spring 1780.

Lt. Col. James Marcus Prevost Wounded in Jamaica

James Marcus Prevost, after successes in the Georgia and the Carolinas, was assigned in early 1780 to Jamaica with a contingent of troops to deal with disturbances in that Caribbean Island. In an engagement there he was wounded. The health conditions in Jamaica debilitated the English troops there. On July 26 Prevost reported to London that most of his officers were in the infirmary at Spanish Town. He feared the “annihilation” of his regiment if they were not moved from their present feverish location to a healthier area. Prevost’s own health was affected, and his condition was in decline. It seems that sometime in 1780 he sent his teenage sons back to their mother at The Hermitage. They undoubtedly reported on their father’s poor health, and Theodosia and others may have come to expect at some point that his condition was terminal.

The War Continues in Bergen County

Through most of the summer of 1780 Washington and the Continental army were on the move through various parts of Bergen County, while efforts were being made to arrange an opportunity, which did not materialize, for a joint attack with French troops on New York City. On their way from Preakness to Kings Ferry on the Hudson River, the Continentals with some 6,000 men and 900 wagons encamped at Paramus and Hoopertown on July 29. The army with 8,000 men in late August was located between Hackensack and Hoppertown. Washington had a detachment work on the badly deteriorated roads in the Paramus area. There are some who maintain that Washington made The Hermitage his headquarters during several of his visits to Paramus, but this has yet to be substantiated.

Peggy Shippen Arnold Visits The Hermitage

In one of the most dramatic turnarounds in the War, Benedict Arnold, among the most experienced rebel generals, hero of the crucial Battle of Saratoga, decided when in command of West Point in late summer 1780 to betray this important Hudson Highland fort into British hands. His new bride of little more than a year, Peggy Shippen who had been a friend of British officers and particularly Major Andre during their occupation of her home city Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-1778, encouraged Arnold in his act of treason. Before the betrayal was completed, Arnold directed Peggy to travel with their 5-month-old child from Philadelphia to West Point. Arnold sent an aide, Major David Franks, to fetch her, and he sent detailed travel instructions. “The fifth night at Paramus… at Paramus you will be very politely received by Mrs. Watkins and Mrs. Prevost, very genteel people.” It seems that Arnold knew, or knew of, these women and was confident of their being helpful to his wife and child at this delicate time.

After the capture of Andre and the discovery of the plot by rebels, Arnold fled to the British lines, leaving his wife and daughter at West Point. Mrs. Arnold dramatically played the role of the injured wife and convinced Washington and Hamilton of her innocence of the betrayal and to allow her to return to her father in Philadelphia with Major Frank. Despite her pass from Washington, Peggy Arnold found hostility along her return route south, often being refused food and lodging. Still, she did find refuge at The Hermitage. According to an account by Aaron Burr, many years after the event, Peggy Shippen Arnold, believing she had a sympathetic Loyalist ear, confessed to her part in the West Pont conspiracy to Theodosia Prevost. At The Hermitage, “as soon as they were left alone, Mrs. Arnold became tranquillized and assured Mrs. Prevost that she was heartily tired of the theatricals she was exhibiting.” She related “that she had corresponded with the British commander, and that she was disgusted with the American cause and those who had the management of public affairs, and that through unceasing perseverance she had ultimately brought the general into an arrangement to surrender West Point.”

After the Continental army had encamped from September 28 to October 6 at Tappan where the trial and execution of Major Andre took place, Washington decided to move his troops south to Totowa Falls. On the way they halted for two days at Paramus, October 7 and 8. It was cold and wet and there was not a drop of rum to be had. In November, Lafayette was at Paramus with a scouting party. He posted a letter to Washington from Paramus on November 28, 1780.

Burr Intensified His Law Studies and Correspondence Between Theodosia and Aaron Became More Serious

In early 1781 Burr, with the return of better health, became deeply engaged in his law studies with Thomas Smith in Haverstraw. He applied himself to his studies from sixteen to twenty hours a day. Before embarking on this regime, Aaron did try to get an additional tutor for Theodosia’s two young sons, who had returned to her from the south, and whom Burr seems to have liked very much. However, his relations with Theodosia through the rest of 1781 seem to have been mostly through correspondence. For much of this period, if not for all of it, Theodosia resided in Sharon, Connecticut. The reason is not clear. It may have been because of health or to avoid New Jersey wagging tongues, but it was at least in part because of her now close relation with Aaron’s sister, Sally Reeves who lived in Litchfield with her husband. Theodosia wrote to Burr in February stating “I am happy that there is a post established for the winter. I shall expect to hear from you every week. My ill health will not permit me to return your punctuality. You must be contented with hearing once a fortnight.”

If Aaron and Theodosia did keep to that schedule, the extant letters from February through November, from her and from him, would be only a very small portion of the total. Few though they are, they do give some insight into the interests that increasingly bound them together – an interest in discussing the ideas of leading thinkers of their time and thoughts touching on the meaning of life, their happiness and their future, as well as how to react to the negative opinions of others concerning their relationship. In May 1781 Theodosia wrote: Our being the subject of much inquiry, conjecture, and calumny, is no more than we ought to expect. My attention to you was ever pointed enough to attract the observation of those who visited the house. Your esteem more than compensated for the worst they could say. When I am sensible, I can make you and myself happy, will readily join you to suppress their malice. But till I am confident of this, I cannot think of our union. Till then I shall take shelter under the roof of my dear mother, whereby joining stock, we shall have sufficient to stem the torrent of adversity.

Burr Completed His Law Studies, Obtained His License, and Began His Law Practice

By fall 1781 Burr and Trout had completed the course of study in the law with Smith. The next task was to get these efforts approved in Albany by the three sitting Supreme Court justices who were empowered to issue the license needed to practice law in the state of New York. Burr had a major problem. Since colonial times there was a requirement that a candidate for the bar complete three years of an apprenticeship. Burr could claim barely one year. However, he pushed on. He moved up to Albany and petitioned the justices. Theodosia had some connections with one of them, Judge Hobart.

Burr used the argument of patriotism stating: Surely, no rule could be intended to have such retrospect as to injure one whose only misfortune is having sacrificed his time, his constitution, and his fortune, to his country.

Nevertheless, the judges delayed a decision for several months. Burr remained in Albany where he took up accommodation provided by one of the Van Rensselaer’s. While he was able to make a visit or two to Theodosia, their communications remained mostly by letter.

On December 30, 1781, Theodosia’s half-sister, Caty, wrote Burr from The Hermitage: “If you have not seen the York Gazette, the following account will be news to you; We hear from Jamaica that Lieutenant Col. Prevost, Major of the 60th foot, died at that place in October last.'” This information did not come as a great surprise to either Burr or to the people at The Hermitage, since it was known that James Marcus was seriously ill. While the news in the Gazette legally opened the way for Theodosia and Aaron to marry as seemed to be their intention, there was no decision to act quickly. Burr was still in Albany attempting to get the license necessary for him to begin a career that would bring him an income. Theodosia seemed hesitant. There was the fact that she was 35 and he was 25, and, despite Burr’s attractive characteristics, Theodosia had to weigh some of his less attractive traits. She arranged to spend time with relatives after the new year.

Then, in January 1782, the three New York Supreme Court justices agreed that time spent in the military would be taken into consideration in judging the preparation qualifications for admission to the bar. This practice in part was adopted because the judges realized that there would be a shortage of lawyers, following state legislation in November 1781 barring from practice all those who could not prove that they were supporters of the Revolution. Thus, Burr’s petition was finally accepted, he was examined, passed, and obtained his license as an attorney on January 19. He then immediately began his study for the next and highest rank in the profession, counselor-at-law. Burr attained this goal on April 17 when the court judged that he had “on examination been found of competent ability and learning.” He now was ready to set up his own law office. He decided to do so in Albany, since New York City was still occupied by the British.

The Double Wedding of Theodosia and Aaron and of Caty and Joseph at The Hermitage, July 2, 1782

While Burr was busy establishing his law office and practice in Albany through spring 1782, he got news that Theodosia’ half-sister Caty and her fiancé, Joseph Browne, a British-born medical doctor and rebel officer in the Pennsylvania line, had set July 2 as the date for their wedding at The Hermitage. Burr arrived there some time before the event. With very little preparation, Aaron and Theodosia decided it was an appropriate time for them to make a like decision and to act on it immediately. It was agreed that the July 2 event would be a double wedding. Thus, after Theodosia’s and Aaron’s friendship had extended over several years, their wedding took place with such short notice that Burr did not have time to get a new coat, Theodosia had to borrow gloves and other items, and they hardly had enough ready cash to pay the minister. They also did not have enough time to arrange for the banns of marriage, so they had to get Governor Livingston to issue them a special license for the wedding.

The marriage ceremonies were held at The Hermitage and were officiated by the Rev. Benjamin Van Der Linde (Leude). Theodosia’s and Aaron’s marriage certificate read: I do hereby certify that Aaron Burr of the State of N. York Esqr. and Theodosia Prevost of Bergen County, State of N. Jersey widow were by me joined in lawful wedlock on the second day of July instant. Given under my hand this sixth of July 1782. B’n Van Der Leude

There were a considerable number of people present including some members of the Suffern family. Theodosia spoke of many friends being present and that the abundance of food supplied by the Browns was all consumed. Both couples left The Hermitage wedding celebration shortly after it was over. The Burrs went to Albany, the place of Aaron’s beginning legal practice.

From Albany Theodosia wrote to Sally Reeves to tell her about the events of the marriage day. You had indeed, my dear Sally, reason to complain of my last scrawl. It was neither what you had a right to expect or what I wished. Caty’s journey was not determined on till we were on board the sloop. Many of our friends had accompanied us and were waiting to see us under sail. It was with difficulty I stole a moment to give my sister a superficial account. Caty promised to be more particular, but I fear she was not punctual. You asked Carlos the particulars of our wedding. They may be related in a few words. It was attended with two singular circumstances. The first is that it cost us nothing. Brown and Catty provided abundantly and we improved the opportunity. The fates led Burr on in his old coat. It was proper my gown should be of suitable gauze. Ribbons, gloves, etc. were favors from Caty. The second circumstance was that the parson’s fee took the only half joe Burr was master of. We partook of the good things as long as they lasted and then set out for Albany where the want of money is our only grievance. You know how far this affects me.

Governor William Livingston wrote “I have but a Moment’s Time to Congratulate you on the late happy Circumstance of your Marriage with the amiable Mrs. Prevost. Confident that the Object of your choice would ever meet Universal Esteem, I have waited impatiently to know on whom it would be placed. The Secret at length is revealed, and the tongue of malice dare not I think contaminate it. May Love be the time Piece in your mansion, and happiness its Minute Hand.”

Judge Hobart and Governor Clinton, both of New York, also sent congratulations to the newlyweds.

After the wedding Theodosia and Aaron settled in Albany, where he developed his law practice and they had a daughter, Theodosia. Following the Treaty of Paris concluding the Revolution and the consequent evacuation of British troops in late 1783, the Burrs moved to New York City. Here Aaron, as well as Alexander Hamilton, quickly became a leading lawyer and engaged successfully in politics. Burr was elected to the New York State Assembly in the 1780s and was named the United States Senator from New York in 1791.

Theodosia managed a succession of increasingly affluent homes in New York City as well as a summer residence in Westchester County near the Brownes and many of her Bartow and Pell relatives; oversaw Aaron’s law office when he was on his frequent legal business trips; and helped raise their daughter with Aaron aiming to make her a very highly educated young person. Husband and wife, in their correspondence, showed a marked concern for the rights of women. Theodosia’s illness (cancer), however, progressed, despite the efforts of the leading doctors in the young nation, and she died in 1794. Aaron Burr would go on to become the Vice President of the United States in 1800 and then lose his political future after a duel with Hamilton in 1804.

AT THE HERMITAGE, A VARIETY OF OWNERS, 1785-1807 - The Cuttings, the Bells and the Laroes

Ann De Visme Maintains The Hermitage, Burr Sells the Adjacent Prevost Property

In the years from 1785 to 1807 The Hermitage and its property had a succession of owners. Following her marriage to Aaron Burr in 1782, Theodosia saw to it that her brother-in-law, Joseph Browne, was named executor of the estate that she inherited from her deceased husband, James Marcus Prevost. It appears that James Marcus had been in debt for 470 pounds to Mrs. Anne Baldwin. Thus, it was arranged that Burr would buy the estate for 520 pounds which would more than cover the repayment of the debt. The transaction took place on May 15, 1785, and the witnesses were John Bartow Prevost, the son of Theodosia, John Cleves Symmes, and William Treason. The 36 acres owned by Ann DeVisme which included The Hermitage where she lived was not affected by this settlement. In 1785 Burr needed to obtain a loan which may have been necessitated to cover the cost of the Prevost property purchase. He held it for several years, and, then in 1789, he sold the 240 acres parcel to William Cutting, a New York lawyer with whom he had engaged in real estate ventures. The price is not known.

Meanwhile Ann De Visme continued to own The Hermitage and its surrounding acres. It is not known how long she resided there. However, by 1794 she was living in New York City, perhaps with one of her daughters. She had rented The Hermitage to William Bell who had married into the locally important Hopper family and was a leading local personage and county official. He was sheriff of Bergen County, 1792 to 1795, and was a militia captain. Then on June 14, 1794, he purchased the house and its 36 acres for 450 pounds. Ann De Visme is listed as the seller and Bartow and Frederick Prevost were the witnesses. In the same year Bell bought from Cutting the 240-acre former Prevost property for 981 pounds.

Masonic symbols on front of The Hermitage

William Bell was both a Methodist and a Mason. The local Methodist Church tradition holds that a small congregation first met in Bell=s house after 1794. Then in 1797, he sold 0.2 acres, probably with a building, to the congregation. They then refitted the building into a church. Some believe Bell also had masonic symbols carved into his Hermitage home, symbols that are still visible today. He was senior warden and treasurer of the Union Lodge in Bergen County.

In 1801 Bell sold The Hermitage, grist and sawmills and 8 acres to Peter Alyea for $1,625. In the following year Alyea sold the parcel to Cornelius Smith for $1,375. In 1803 Smith sold the same piece to James Laroe for $1,750. In 1804 Bell sold 93 and 151 acres to Laroe for $3,855. Thus, the properties were again brought back together. Laroe, was a member of a long resident French Huguenot family in the Paramus area and in other parts of Bergen County. Earlier Laroe was the wife of Johannes Traphagen the first owner of The Hermitage properties. James Laroe in these early years of the 19th century was a local innkeeper. In 1807 Laroe sold The Hermitage and 55 acres to Dr. Elijah Rosegrant for $2112. Laroe retained the mills.

THE ROSENCRANTZ FAMILY AND THE HERMITAGE – 1807-1970

Dr. Elijah Rosegrant (Rosencrantz) Bought The Hermitage in 1807

Elijah Rosegrant who bought The Hermitage in 1807 was a fourth generation American. His grandfather, Harmon Rosenkrantz, a member of a Dutch family engaged in fishing work in Bergen, Norway came to New Amsterdam around 1650. Here he married the widow, Magdalen Dircks in 1657, and together they moved north to the Hudson River village of Catskill. They had nine children, and by 1680 the family had moved some miles west to the Ulster County township of Rochester where they developed a pioneer farm. Their first son, Alexander, married Marietjen Dupuy, a French Huguenot, and together they had seven children. In 1731 this Rosencrantz family bought fertile frontier land in the Delaware River Valley near Walpack in Sussex County, New Jersey. Their son, John, Elijah’s father at age 21 was given a farm of over 500 acres.

John Rosencrantz became a community leader and a colonel in the Revolution. He and his wife Margaret De Witt, from an influential New York State family had 14 children and a few slaves. One of John and Margaret’s sons, Elijah, attended and in 1791 graduated from Queens College (Rutgers) in New Brunswick, the only one in his family to do so as far as is known. He, in some way became involved with Bergen County, and he would use as his family name, Rosegrant.

After graduation, Elijah decided to study theology and attained his license to be a minister and preach in the Dutch Reformed Church in 1894. He preached at the Paramus church but did not get a call. While he could have found employment as a traveling minister, he decided that he did not like that style of life and that it would not bring him an adequate income and stability. He then accepted a position as head of an academy in Bergen (Jersey City), for a year, following which he decided to train to be a physician, a profession in which he felt he could also serve people. After two years of study and apprenticeship, two New Jersey doctors examined him, and judged that he was qualified to practice as a physician and a surgeon. Two judges of the New Jersey Supreme Court in October 1799 issued his license to practice in the state of New Jersey.

The new doctor decided to reside and practice in Bergen County. Here, he at first lived with a younger brother, Simeon who had come there with his 19-year-old wife, Sarah Shoemaker, both from Walpack. Simeon would apprentice with Elijah and after 1807 would return to Sussex County as a physician. Before leaving, Simeon and Sarah had a son who in 1807 was christened in the Paramus Reformed Church. They would keep in touch with Elijah, and one of their sons, Charik, born in 1811 in Walpack, would marry Mary Ann Hopper of Ho-Ho-Kus. This new family would reside and raise their family there close to The Hermitage.

In 1803 Major William Bell who had been county sheriff and had lived in The Hermitage appointed Dr. Rosegrant as Surgeon Mate of the Bergen County Militia. This appointment was confirmed by New Jersey Governor Joseph Bloomfield. From 1804 forward Elijah began to borrow money to buy pieces of land, culminating with the purchase of The Hermitage from James Laroe on June 20, 1807. Laroe did not include the mill sites on the property but kept them for his own use.

Elijah Rosegrant Married Caroline Suffern from Leading Local Family

Just before his purchase of The Hermitage, Elijah married Cornelia Suffern, daughter of John Suffern, the leading figure in the area of New York (Rockland County) adjoining northern Bergen County. The wedding on June 14, 1807, was held in New Antrim (part of a patent earlier owned by James Marcus Prevost and which later came to be called Suffern) and the signed witnesses were Judge John Suffern, Simeon Rosencrans, John Hopper, Christian Wanamaker, and George Brinkerhoff. At the time of the marriage Elijah was 41 and Cornelia was 34.

Elijah Was a Country Doctor in Bergen County

Elijah was one of the relatively few physicians in Bergen County in the early decades of the 19th century. He cared for families, mostly through house visits to their farms or their homes in villages in the area surrounding Ho-Ho-Kus. Dr. Rosegrant treated people suffering from accidents, set bones, purged patients, gave medicines for fevers and delivered babies. For the latter, the charge was $2, larger than the charges for any of his other services. To reach his patients, Elijah had a gig and a brown horse which was also used for the family’s pleasure sleighing in the winter. Elijah ordered his medicines usually from New York City, and he made efforts to keep up with his profession. He bought books, and we have record of his ordering in 1826 a medical dictionary and Dr. Benjamin Rush’s version of Thomas Sydenham’s (the “British Hippocrate”) textbook on medicine. In 1818 Abram Hopper, 21, of Ho-Ho-Kus, after gaining an academic education in New York City, studied medicine with Dr. Rosegrant for a year. Hopper then began a practice in Hackensack. Also, in 1818 Elijah met with 11 other doctors in an unsuccessful effort to form a Bergen County medical association. An ongoing association was established only in 1854.

According to an account book of Dr. Elijah, in a one-year period (1830), he made 549 house visits to 110 local families. His income from these visits was $538. It is not certain that this was his entire income from his medical practice, but if it was it indicates the middling income and status of a country doctor at this time and indicates why Elijah became engaged in other revenue producing activities. Studies show that $538 would have been about equal to the income of a trade’s foreman. Thus, it was above the average of a wage-earning worker, but did not make one wealthy, comfortable or even “middle class.” But Elijah did search out other sources of income. He not only needed finances to take care of his house, family, and servants, but he did incur expenses in the education of his sons, particularly John who studied at least three years away from home, one year at an academy for classical studies and two years at Rutgers Medical College. At the latter the cost for lectures, books, board, and clothing was about $400 per year. Additionally, Elijah, at least to some extent, took part in the social life of his community. It was noted in an 1828 correspondence that he attended the Washington Ball at the Zabriskies.

Elijah also Farmed, Bought Land and Built a Cotton Mill

For one thing, Elijah continued working on a farm and a sawmill on The Hermitage property. He had several cows, some 20 fowl, a yoke of oxen, and produced a considerable amount of buckwheat, rye, hay, corn, and potatoes among other products. This endeavor would go far in feeding the household and probably provided produce for the market. He had a gun and went hunting. Elijah bought additional pieces of land for The Hermitage and then rented part of these out for added income. He also was drawn to gamble – he often bought lottery tickets – and he bought two 160-acre tracts of land in Illinois in 1818, one for $50, as a speculation. In 1828 he bought some land in Tioga County in upstate New York from a Suffern in-law and then sold it in 1830.

Then, after Elijah’s neighbor, James Laroe, had converted an old bark mill on the Ho-Ho-Kus Brook into a paper mill in 1826 and Andrew Zabriskie had built a cotton mill downstream, Elijah in 1828, acquired property between them with the thought of building a cotton mill. Even though Laroe had enlarged his mill and built a new mill race upstream from Rosencrantz in 1829, Elijah went ahead in the following year with the construction of a mill race of his own, a wheel pit and a cotton mill as rental property. This strained Elijah’s resources, because as son John noted in a letter to his brother George, “we cannot raise cash enough to pay the shoemaker bill.” Nevertheless, Elijah did succeed in finishing the mill by 1830, and in that year signed a 10-year lease with Abraham, Henry and Peter Prall to operate the mill as the firm of Prall and Brothers for $400 a year rent. They began operation around December 1830. In April 1831 a flood damaged the mill, it temporarily ceased operation, but was restarted by 1832.

As both Rosegrant and Laroe, together with others in Bergen Count, were enticed by the possibilities of economic gain through the just emerging industrial revolution, their endeavors brought them into conflict in the years between 1825 to 1830. Elijah brought Laroe to court over road obstructions and the changing of the direction of the flow of water in Ho-Ho-Kus Brook. Although he obtained the legal services of Philemon Dickerson, one of the top lawyers in New Jersey, the court judged that Laroe’s obstructions did not prevent Rosegrant from moving around his property nor deter his mill interests.

Elijah and Cornelia Rosegrant Family Life

Elijah and Cornelia, though married relatively late in life, had four children, all sons. This family, however, had a markedly smaller number of children than the families from which they came (14 and 12). The sons were John born in 1809, George Suffern in 1812, Elijah II in 1814 and Andrew in 1817. Andrew died young at age of 2 in 1819, not an unusual occurrence at this time, even in the family of a doctor. While the other boys received a classical type of education at home, John, for a short time, and George, for a longer period, were apprenticed to their second Cousin Tom Suffern who ran a retail store in New York City.

John, who seems to have been favored by the family, at least in terms of education, was enrolled in a classical academy, probably in New York City, and then at the Rutgers School of Medicine also in New York. This required an outlay of money from Elijah, not only for John’s tuition, but also for his room, board, and other expenses. The years were 1824-1827. For these years when John was in New York, there are several extant letters from Elijah to his son. They give us some idea of Elijah’s values. He constantly urged John to put sustained efforts into his study and to read. He thought highly of a classical education, and when this was no longer possible for John, he accepted a medical education as second best, but still valuable. While Elijah recognized the need for exercise and recreation for his son, he strongly warned that “bewitching frolics,” the pleasures of youth, the diversions of the city, and attractive company should not interfere with his primary task of study. In addition to learning from lectures and books, the father frequently reminded his son that knowledge of the world was indispensable to his becoming useful to himself and to society. John was to derive useful information from everything he saw and heard. Elijah approved of his son’s spending some time in dancing school, if it was proper, probably for its social utility. The father urged John to attend church, give respectful attention to religious instruction, express no critical ideas or opinions, refrain from arguing on religious subjects, but reserve to himself the right of private opinion. At church he could meet good company and observe good manners. Elijah encouraged John to respect others, his equals, and his superiors. The cardinal virtues that Elijah urged on his son were honesty, justice, temperance, and prudence.

Another concern of Elijah was the countering of the prevalent focus of many in the country on “ghosts, specters and hob goblins.” In a statement “If the Hangings Flutter” in 1828, he gave examples of current “supernatural” beliefs and judged them as absurdities. He put the blame primarily on persons of the lower classes and from poor early education. “Tis education forms the common mind, Just as the twig is bent the tree inclined.”

We do not know much about Elijah’s wife, Cornelia, but she did have three sons to raise and a household to run. She had help from servants. In the letters from Elijah to John, there is mention that Cornelia did get to Paterson, but a promised trip to visit her sons in New York City was continually postponed. She seemed increasingly unwilling to leave her home.

African Americans at The Hermitage