North Jersey Rapid Transit - The Ho-Ho-Kus Trolley

North Jersey Rapid Transit - The Ho-Ho-Kus Trolley

The public referred to it as “The Trolley” or the Suffern Trolley. It ran in and out of Ho- Ho-Kus from late 1909 to 1929. It was a single-track system with bypass tracks to allow for two-way traffic. When fully operational, the route started in East Paterson (Elmwood Park) with stops in Fair Lawn, Glen Rock, Ridgewood, Ho-Ho-Kus, Waldwick, Allendale, Ramsey, Mahwah and Suffern, New York. (16 miles).

The Board of Directors had additional routes planned to expand the system to Tuxedo, Greenwood Lake, Spring Valley, New York and Hoboken, New Jersey.

Construction started in August 1908. Various delays were experienced because land acquisition for the right of ways had not been all secured. Road crossings were a problem in Ridgewood and property owners wanted more money. In addition, the Erie Railroad crossings had not been properly concluded. But very limited nonrevenue service was reported by late October 1909 to Ho-Ho-Kus. Regular revenue service was in place by mid-June 1910. Service to Mahwah began in early 1911. Suffern service was established by 1912.

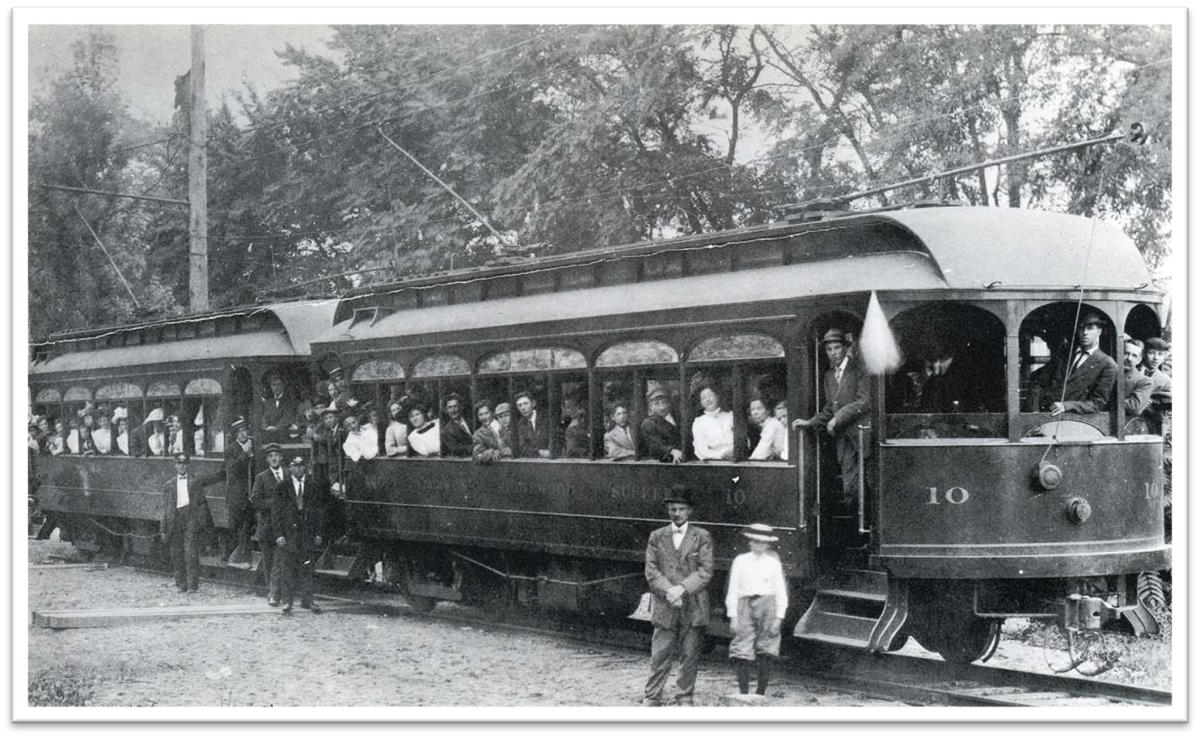

Ho-Ho-Kus was the center of the system. The headquarters building was situated in Ho- Ho-Kus off East Franklin Turnpike. The building was the largest building in the Borough at the time. It was 145 feet wide with entrances at both ends of the car barn. This allowed cars to run through the building thus making it efficient for the movement of equipment. The barn design allowed for the accommodation of 9 cars inside. The tracks inside the barn were built on a slight grade to allow snow and rainwater to run off the cars and drain out of the building. The structure was constructed with a steel frame, red brick, and a reinforced concrete roof to make the building fireproof. It contained various support facilities to maintain the 11-car fleet. (8 passenger cars, 1 work car, 1 fleet car and 1 gondola car) The freight type cars were usually found on the equipment storage truck in the back of the building. The work car had 4 one hundred hp motors and would be stored inside at night or during bad weather.

The building included a large sub-station, coal fired heating plant, machine shop, and a 3-bay car barn with repair pits. (Some areas of the building were two stories.)

The facility faced east, and the main line of the trolley ran in front of the building. Also in the front portion was the superintendent’s office, operations office, secretary’s area, crew office with rest room and locker area and a heated passenger waiting area. It was the only heated waiting area on the system.

At the north end of the building was a road off East Franklin Turnpike, a flagpole and flower garden, maintained by the secretary and the barn crew, and three tracks off the bypass leading into the barn. (The frontage on the Turnpike was 103 feet.)

Down at the south end were four tracks leading off the bypass. These extended into the car barn, the fourth track went around the back and ended. This was the track for the work cars and related equipment. Also in the front area was the single track mainline and a bypass track. (Bypass track allowed trolleys to pass each other in opposite direction) An unheated passenger waiting station, was on the east side of the main track. Additional small support and storage structures were located south of this passenger platform. The right of way leading in and out of this complex was 67 feet. The rest of the right of way, system wide, was 60 feet.

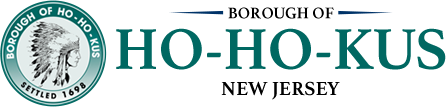

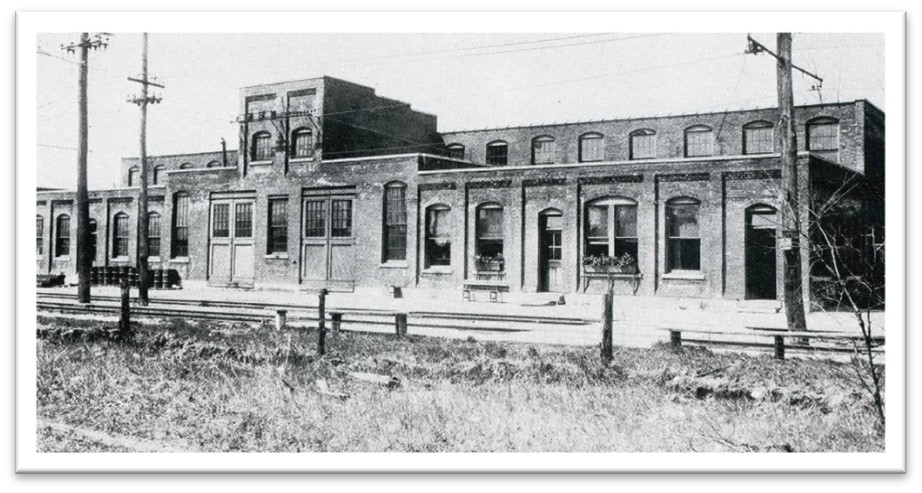

The Ho-Ho-Kus location was the center of the system. It occupied a little over an acre of land along East Franklin Turnpike. Some historians have stated this company was the town’s biggest industry. The entire system was built to the highest standards of the day. The company did not skimp on building quality, equipment, or the trolley fleet. The trolley cars were believed to be one of the best anywhere. They were constructed by the Jewett Car Company, Newark, Ohio. They seated 44 passengers but were known to have carried over 150 passengers with ease on special race days. The cars were mostly constructed of wood and were painted dark green. Striping and lettering were in gold. Each car was 49 feet in length, 9 feet 9 inches wide and 13 feet high from the ground. Eleven windows were on each side plus three at the front and rear end. They were originally heated by a coal fired hot air unit. The heaters were later replaced by electric ones which were cleaner and needed less maintenance. The under carriage was steel. Each car operated with four 46 hp traction motors. The car weighed about 25 tons. These revenue service cars were even numbered 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, & 24.

This trolley design had not been seen in this part of the country. It was mammoth in size, pleasant in appearance and built for comfort at a cost of $8,000 each. The cars ran on 75lb. rail which was excellent for this large trolley.

A third rail shoe was later attached to the southwest side of the trolley’s truck. This device had two functions: first to improve the reliability of the block signal system for the entire trolley line, and second function was to trip the street crossing signal system that the trolley traveled.

By July 4th, 1910, only four cars were available for service. It was the first major test for providing on time dependable service. It was the traditional race day at the Ho-Ho-Kus Race Track. The system and its people performed extremely well. It set the tone for acceptance by the public. The trolley was very popular even though it did not pass Ho- Ho- Kus until 1911. Race days, holidays, and County Fairs and Carnivals kept the trolley a major draw for several years.

People would take rides just for fun and enjoyment. In the hot summer months, people would go for a ride to cool off. For young people, at that time, it was a great way to go on a date.

Over 25,000 people rode the trolley in the first two weeks of limited operation.

In Ho-Ho-Kus there were several streets with a crossing signal, East Franklin Turnpike, Warren Avenue, Sheridan Avenue, and Hollywood Ave. Sherwood Road and Lakewood Avenue did not exist at this time. Elmwood Avenue only went as far as Enos Place. The upper section of Blauvelt Avenue known as Henry Street did not cross the right of way.

There were two official trolley stops in Ho-Ho-Kus, East Franklin Turnpike and Sheridan Avenue. Because the employees were so enthused about the trolley, the customers, and the communities they served, the trolley operators were known to pick up and drop off people in between stations. Story has it that the pastor of St. Luke’s Church, Father Pinder, was picked up in this fashion. He would conduct Sunday and other religious services and when necessary, would travel by trolley from behind St. Luke’s to St. Paul’s Mission Church in Ramsey. This new system allowed the pastor a better way to travel up north starting in 1911.

The Ho-Ho-Kus Board of Education arranged for high school students to travel to Ridgewood High School via the trolley. The students would receive compensation for their trips at the end of each calendar year from the Board.

By 1911 the Trolley Company received permission to have multiple car “consists” to handle heavy traffic demands. Usually two car “consists” were the norm on special event days at the Ho-Ho-Kus Race Track. There were times that three car “consists” were formed but these arrangements were rare.

North Jersey Rapid Transit planned a series of expansions, due to the enthusiastic acceptance of the trolley. Most historians and trolley fans are not aware that one of the expansions was acted upon. The Company planned to expand the line to Greenwood Lake, from the Suffern New York station. The other was to Spring Valley New York through the Saddle River Valley from Ho-Ho-Kus. In order to accomplish these expansions, the Company needed land for the spur line as well as building a new service and storage facility. The Company purchased an additional 7.5-acre plot in Ho-Ho-Kus in 1911. They purchased the Peter Busch farm on Sheridan Ave. The property, buildings, and grounds remained in the hands of North Jersey Rapid Transit for many years before being taken over by an employee at the end of 1925.

No other plans came to fruition because of a deadly accident in July of 1911. Three people were killed, including the trolley superintendent and sixteen people were injured in a head- on accident in Ridgewood. The Company moved quickly and successfully to settle all claims. The litigation forced the company into receivership and bankruptcy in August of 1911.

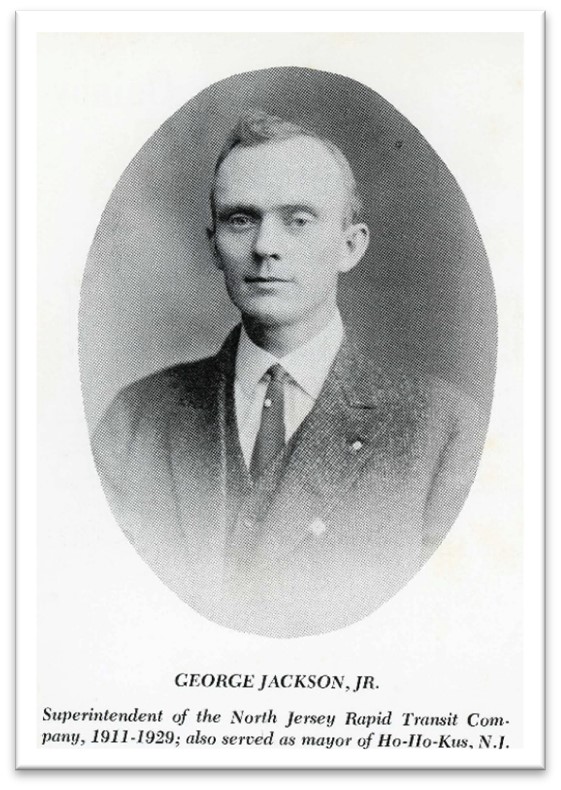

A new superintendent, George Jackson, was appointed as a result of the accident. He was a Ho-Ho-Kus resident, with an extensive engineering background. He lived in the Peter Busch farmhouse, 110 Sheridan Avenue, which was owned by the trolley company. One of his early projects was to construct a trolley station near the north border of the farmhouse property. It was known as the Sheridan Avenue stop. It was a successful and popular station site.

In late July 1911 another fatal accident occurred. This one was in Ho-Ho-Kus. It seems that a man was walking in the right of way on Warren Ave. and did not get off the tracks, ignoring the warning and whistles. Despite these tragic incidents, the trolley was very popular. On race days and special events at the Ho-Ho-Kus Race Track, the trolley experienced very high patronage.

By 1912 the system was the major way to travel to the racetrack. The track held all types of events to draw the public. This resulted in a high demand of service from the trolley. The biggest event of this year was the Aero Meet, with hot air balloons, (see Ho- Ho-Kus Race Track – Historic Element) sky diving and one of the first air mail deliveries in New Jersey.

The construction of the trolley line over the New York State border to downtown Suffern was also completed that year.

In 1913 thieves were busy stealing the overhead copper electrical cables. The Ho-Ho- Kus headquarters was busy sending the maintenance car and crew to replace the damaged areas. This was done with minimal interruption of service. Headquarters and the local police worked diligently to stop the thieves.

Also this year, Ramsey, Mahwah, and Suffern petitioned to extend trolley service including Saturdays and Sundays.

The 1914 Bergen County Fair was a very big hit for the track and the trolley company. The 3 car consists were put to the test 4 of the 5 days of the fair. Operating out of Ho- Ho- Kus, most of the 3 car consists operated to the south while only a few traveled north to Suffern.

From 1915 to 1917 The Bergen County Fairs were the highest volume times for the trolley. Other track events, during the year, kept the employees busy. The Trolley Company was also carrying a small amount of freight up and down the line which also added to the company income.

Mother Nature challenged the entire North Jersey Rapid Transit organization in 1915. On Monday, December 13th, the worst late autumn snowstorm tested the employees, the equipment, the system and the design and function of the Ho-Ho-Kus facility. The area was buried under several feet of heavy wet snow. Drifts of 4 to 5 feet were reported in some areas. These drifts were caused by winds of up to 70 MPH. Communications were lost in many areas, but the trolleys continued to function out of the Ho-Ho-Kus headquarters.

The Erie Railroad struggled to operate, and by late afternoon could no longer provide reasonable service past Paterson.

The employees of the Trolley Company reported to headquarters. Many came in on their own; others were called back to work. Employee spirit, enthusiasm, concern for customers and fellow employees were put to the test.

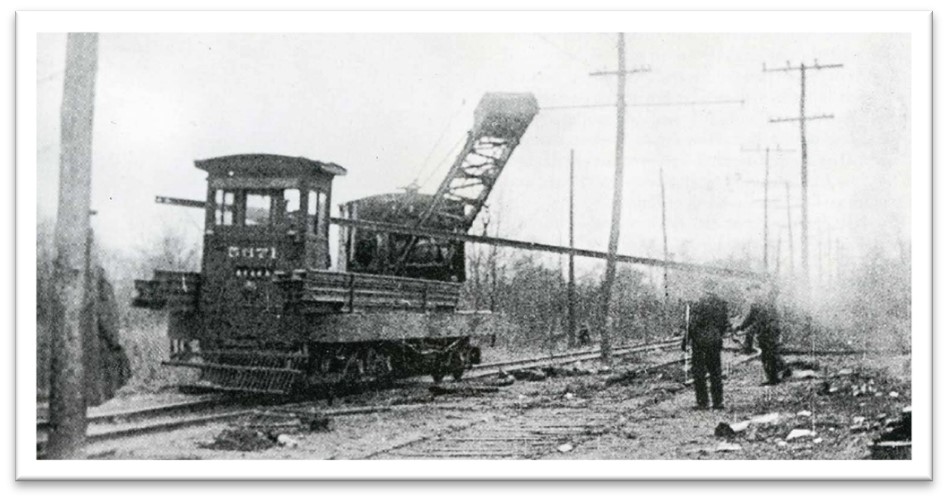

A work car, which was equipped with a plow installed on both ends, operated out of Ho- Ho-Kus. It plowed continuously from late Monday afternoon until late on Tuesday. It plowed north and south of headquarters. The southern tier required periodic plowing followed by revenue cars. This process kept the tracks in reasonable running service. North of Ho-Ho-Kus was a different challenge. The tracks had to be plowed all night and day. The mechanical department was hard pressed to keep the equipment in running order and remove snow and ice from the unprotected traction motors that night.

Service north of Ho-Ho-Kus operated on a modified schedule for two days. Passengers were transported to the headquarters station where they transferred to another revenue car. The balance of the trip south was less complicated and smoother. By this modified schedule even the Erie Railroad customers were able to get to Paterson to get on an operating train.

During this storm period, employees were out assisting customers, clearing station platforms, and keeping the paths functioning at the bypass tracks. This effort was not unrewarded as new passengers continued to travel on the trolley system.

The Paterson Sign Company erected a large metal green sign advertising the Bergen County Fair. It was installed on East Franklin Turnpike in full view of passengers on the trolley line.

At the end of August 1917 everything changed. The country was going to war. The North Jersey Rapid Transit was on a war footing. Men went to war and the trolley company needed conductors and inside people to handle the trolleys business, so at the start of 1918 several females started handling the duties as conductor.

On Sunday April 6, 1918, (1st anniversary U.S. entering WWI), George Jackson arranged the entire trolley fleet in a line up outside the headquarters building. The lineup extended across East Franklin Turnpike. The trolley company employees, at 8 PM, blew the whistles of all the cars assembled. In addition, they extended the arc lights into the sky and rang the bells of the fleet. They were then joined by the Ho-Ho-Kus Fire Department ringing the large fire bell in the tower down the street. The Ho-Ho-Kus Bleachery (Hollywood Ave.) joined in with its steam powered whistles. This alert to the public lasted for 5 minutes. George Jackson was asked to create a campaign for “Liberty Loan Drive” to sell war bonds to support the war effort. All towns in the area conducted various programs for the “kick off drive”. Ho-Ho-Kus exceeded its quota and was able to display its quota flag.

By 1920-21 the public was looking for change. The war was over and people started back to the Track. Now the big days for the trolley were Memorial Day, 4th of July, and Labor Day. Auto racing had taken hold as the sport of interest.

The bus companies were trying to make inroads on the trolley business. They were blocked for several years by the Mayor of Ho-Ho-Kus who was also the Superintendent of the North Jersey Rapid Transit Company. By 1923 the resistance broke down. Many roads were paved, and new ones were being built. Automobiles were popular on the new roadways. People loved to drive in the car. The bus companies were more plentiful now that they had good roads to travel. In addition, many of the Trolleys rail lines were on the outskirts of the communities it served. The bus company carried passengers to the business center of the communities. This service was a major competitive advantage.

The trolley enjoyed strong public support and made money until the middle of 1925. A bus company came into the area that competed for the same customers. The bus line alternated its schedule to beat out the trolley timetable. The trolley lost customers and revenue.

Despite the record crowds attending the special racetrack events by trolley in 1926, the Company was in financial trouble. It could not pay the electric power bills. Public Service took over all of the North Jersey Rapid Transit System and its operations. It extended the trackage into downtown Paterson, adding 2.75 miles to the trolley route. It was now known as Public Service Rapid Transit.

Another significant move took place in 1926. George Jackson, Superintendent, realized that this trolley line was in serious financial trouble. So, he obtained the land the trolley company owned on Sheridan Ave (Peter Busch farm). He transferred the title to his wife, Elise.

The acquisition and extension into Paterson did not help this transportation company. Revenue and customers were now declining rapidly. At the end of 1928, Public Service Rapid Transit received permission from the State to terminate operation at the end of the year. George Jackson, Superintendent, shut down the power plants on New Year’s Eve 1928; and the era ended.

But January 2nd, 1929, the power was back on. Public Service hired contractors to tear up the tracks and remove the trackage from Suffern New York to East Paterson. The process started in Suffern and worked its way down the right of way. The Ho-Ho-Kus facility was very busy with the equipment moves until the end of February when the rails were removed from the yard barn and by-pass track. By March the rail was removed in front to the headquarters building. The abandoned headquarters building remained in place until the early 1940’s.

Over its time of operation, the North Jersey Rapid Transit Company employed over 90 people. Almost all came from the towns that surrounded the headquarters building on East Franklin Turnpike.

Historians and rail fans have stated that Public Service sold the excess rail to Russia, and the rail was used in building the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Engineers state that the New Jersey Rapid Transit rail could not have been used in regular railroad service. The 75 lb. rail was very good for trolley service, but not safe for railroad requirements. They do state that the rails were most likely used in the shops, barns and standby trackage. The 75 lb. rail would work very well and safely for this purpose.

Items of Interest:

Remains of the trolley system are still evident in Ho-Ho-Kus today (the Public Service right of way in town was the route of the trolley tracks):

- A set of trolley tracks are still in the sidewalk on East Franklin Turnpike.

- The trolley bridge over the Zabriskie Brook is still in place and functions. It is located behind 16 Lakewood Avenue

- The accountant/bookkeeper’s house still exists at 125 Elmwood Ave.

- Superintendent Jacksons house (circa 1830) is still used as a residence at 110 Sheridan Avenue

- Remnants of the Sheridan Ave. Trolley Station have survived and are maintained.

- The land that the Trolley Company purchased for future expansion is still an anomaly on the Municipal land use and Tax maps.

Daisy McElroy was bookkeeper/accountant and company record keeper for North Jersey Rapid Transit on East Franklin Turnpike. Her husband, John McElroy, was employed as a mechanic and served in the back shop. It has been reported that he also assisted as a motorman running the trolley from time to time. By 1927 John McElroy was doing police duties in Ho-Ho-Kus. He became Police Chief in 1932 and served until 1955.

The land that North Jersey Rapid Transit purchased in 1911 and controlled by the Jackson’s was the farm of Peter Busch. The farm was almost 304,000 square feet (about 7.5 acres). It extended from Sheridan Ave. east to about Lakewood Ave (on today’s map). Portions of the land were sold over the years. It provided the land for the extension of Elmwood Ave. past Enos Place, thus creating building lots on Lakewood and Elmwood Avenues. This selected selling allowed the owners of the property on the south side of Hollywood to enlarge their lots. Some of these unusual lot sizes still exist.

Daisy and John McElroy acquired 2 plots of land from North Jersey Rapid Transit in 1924 after Elmwood Ave. was extended past Enos Place. The property is known as 123 and 125 Elmwood Ave. They built a home at 125 Elmwood Ave for $6500. They followed up with an investment of $400 for construction of a detached garage. In 1926 Daisy planted an oak tree in the back yard but was told that it would never grow. Today the home is still a nice residence, and the oak tree is now 4.5 feet in diameter and spreads out 90 feet.

George Jackson was always interested in civic affairs of the Borough. He was a member of the Ho-Ho-Kus Board of Education for several years. In the late teens, he served as councilman, and in 1920 to 1923 he was Mayor. He remained Superintendent of the Trolley Company during his term as Mayor. In 1934 he was elected back as a councilman.

The Superintendent’s house at 110 Sheridan Avenue is still used as a residence. The home that Mr. & Mrs. Jackson and the North Jersey Rapid Transit owned occupied 1.5 acres. The Sheridan Ave. Trolley Station was also located on this site.

The property has since been subdivided in 1999 and 110 Sheridan Ave. now occupies four tenths of an acre. The house has had some renovation over the years but is still basically the same structure. The Superintendent had sold off some of the land before and after his wife took title. This quasi ownership helped the Jacksons with their municipal taxes. They did not have to pay personal property taxes. They claimed that North Jersey Rapid Transit owned the property and many items in the house, including their car, so they were exempt in many areas of the tax code as it existed at that time.

In 1929 when the Trolley ceased operation, Jackson retired. Apparently, he had been preparing for the closing down of the system since the early 1920’s and had been studying landscape architecture. Gardening was a hobby of his and his wife. Over the years the work cars delivered soil, stones and other materials to assist in developing a first-class garden at the Sheridan Avenue house.

He had several accounts already in place. He had designed and constructed a number of gardens on estates in Bergen, Passaic, and Sussex Counties. In addition, he was the landscape architect for the original Public School on Lloyd Road. He was regarded as one of the finest landscape engineers in the North Jersey area. Tourists came to Ho-Ho- Kus to see the fabulous George Jackson Gardens.

George Jackson’s passion for gardening was recognized in 1928. He received the Grand Award in the Estate Class in the “New York Worlds” Better Lawn and Garden Contest. His property on 110 Sheridan Avenue was considered the best Estate Landscaping in the 50- mile radius of New York. That same year he received a gold medal for the most attractive estate in Bergen County.

Mrs. Jackson operated a tea room at the house during the garden tourist season. This business complimented their exquisite garden presentation and helped bring in more guests and clients.

The magnificent Jackson gardens that were highly recognized around the state and region no longer exist. The elaborate area with special furniture lasted until the mid to late 1940’s. George Jackson passed away in 1935 and Elsie Jackson maintained the gardens and the historic home. She sold the property in 1936.